Nader Shah, ruler of Persia, after having beaten his Afghan enemies, looked down upon the richness of the Mughal empire in India with interest and soon decided upon an attack.

He found a pretext for invasion in the supposed sheltering of Afghan refugees by the Mughals and then moved east.

He deftly defeated the defensive garrisons at the Khyber pass by attacking them from two sides and then descended onto the Ganges plain.

Muhammad Shah, the Mughal emperor, gathered a vast army and moved to block him at Karnal, a few days marching from Delhi.

The Mughal army may have numbered as many as 300,000 men, though only about 1/4 - 1/3 of them soldiers.

Most were infantry; a minority cavalry; there were also 2,000 elephants and 3,000 guns.

However many of the men had little experience or training and the guns were far too heavy and slow to be used as effective field artillery.

The Persian army had only 55,000 men, including 20,000 musketeers and a number of zamburaks, light artillery guns mounted on camels.

Most of them were well drilled and experienced from Nader's numerous campaigns.

During some initial skirmishes the Persians captured the fortress of Azamibad and some of the Indian artillery.

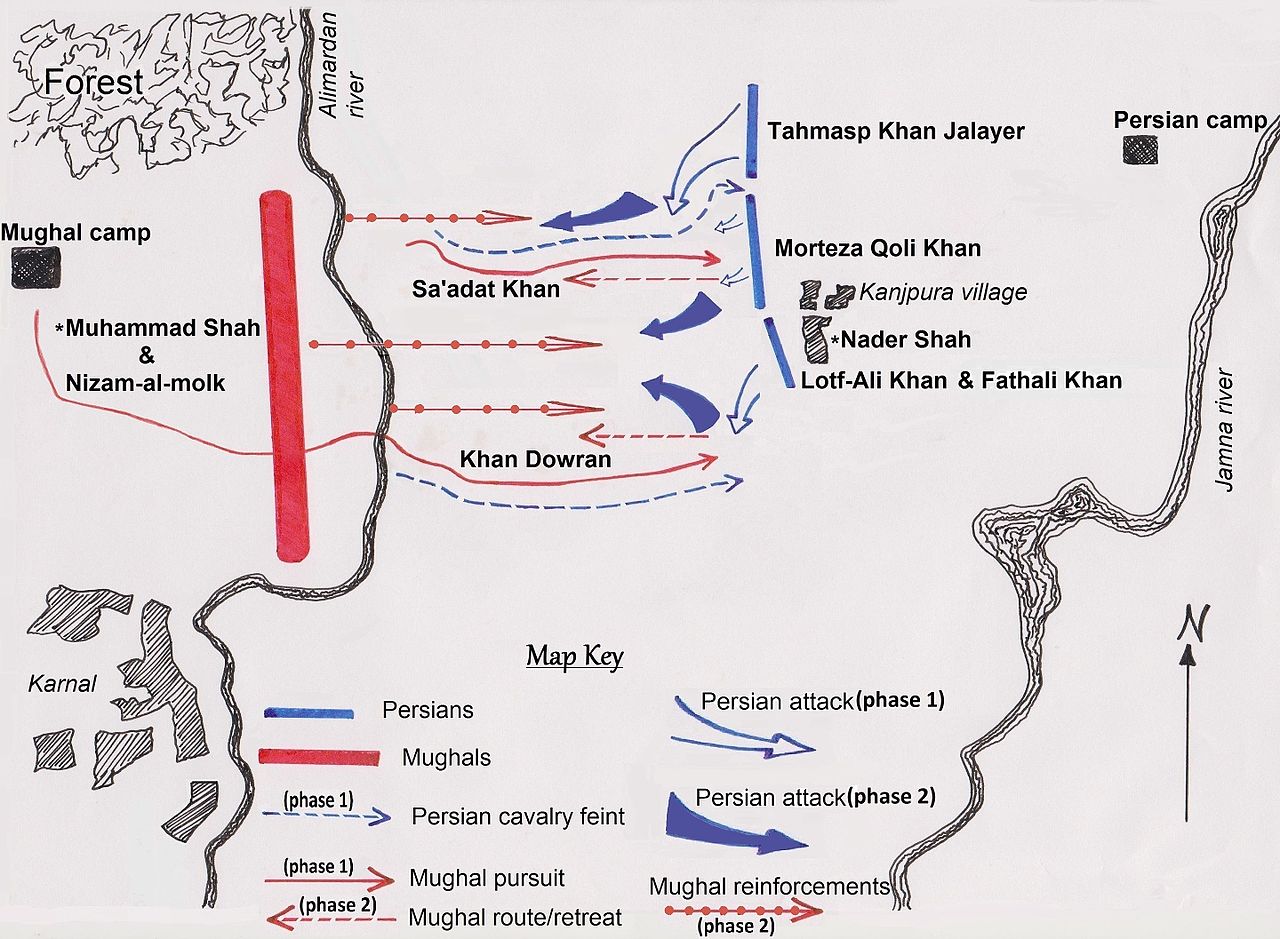

Then they took up position between the Alimardan and Jamna rivers.

Scouts reported Mughal reinforcements under Sa'adat Khan approaching via Panipat in the south and Nader Shah decided to use him as bait.

While Sa'adat Khan and his vanguard arrived in the main Mughal camp, the Persians attacked the rear of the long column and captured the baggage.

Sa'adat Khan immediately turned around, rushed back and drove off a small number of Persian cavalry.

He smelled victory and called for reinforcements.

Mughal commanders like Khan Dowran pleaded caution, but were accused of cowardice by Muhammad Shah and joined the counterattack.

During the battle Mughal reinforcements reached the front piecemeal and in confusion, rather than in a conscious movement.

The Persians lured Sa'adat Khan and Khan Dowran further out to an area around the village of Kanjpura, where they had taken up fortified positions.

Gunfire from the musketeers and zamburaks wreaked havoc among the Indians, who fought valiantly nonetheless.

Then the Persian right wing, until that time unengaged, wrapped around the fighting and attacked the Mughals in the left flank.

After a couple of hours of fighting Khan Dowran was heavily wounded and Sa'adat Khan forced to surrender.

The Mughal forces disintegrated and fled westwards.

The Persians pursued up to the Alimardan river.

The news of the defeat of the cream of the army broke Mughal morale and some troops started plundering their own camp.

Meanwhile Nader Shah sent light troops around them to cut off their lines of communication.

The Indians lost between 10,000 and 20,000 men, a small fraction of their army, but it included the best troops and several hundred officers.

The Persians lost no more than 400 killed and 700 wounded.

Though the main Mughal army was still untouched, its power was broken and its leaders surrendered to Nader Shah.

The latter wrested an indemnity from Muhammad Shah, but later changed his mind, marched on Delhi and ordered the emperor to levy taxes.

When a rumor spread that Nader had been assassinated, the population rebelled.

Nader struck back hard, killing 30,000 people in just a few hours.

After three months he marched home, heavily burdened with treasure.

The battle hastened the decline of the Mughal empire, brought war between the Persian and Ottoman empires

and might have paved the way for the British to conquer India.

War Matrix - Battle of Karnal

Age of Reason 1620 CE - 1750 CE, Battles and sieges